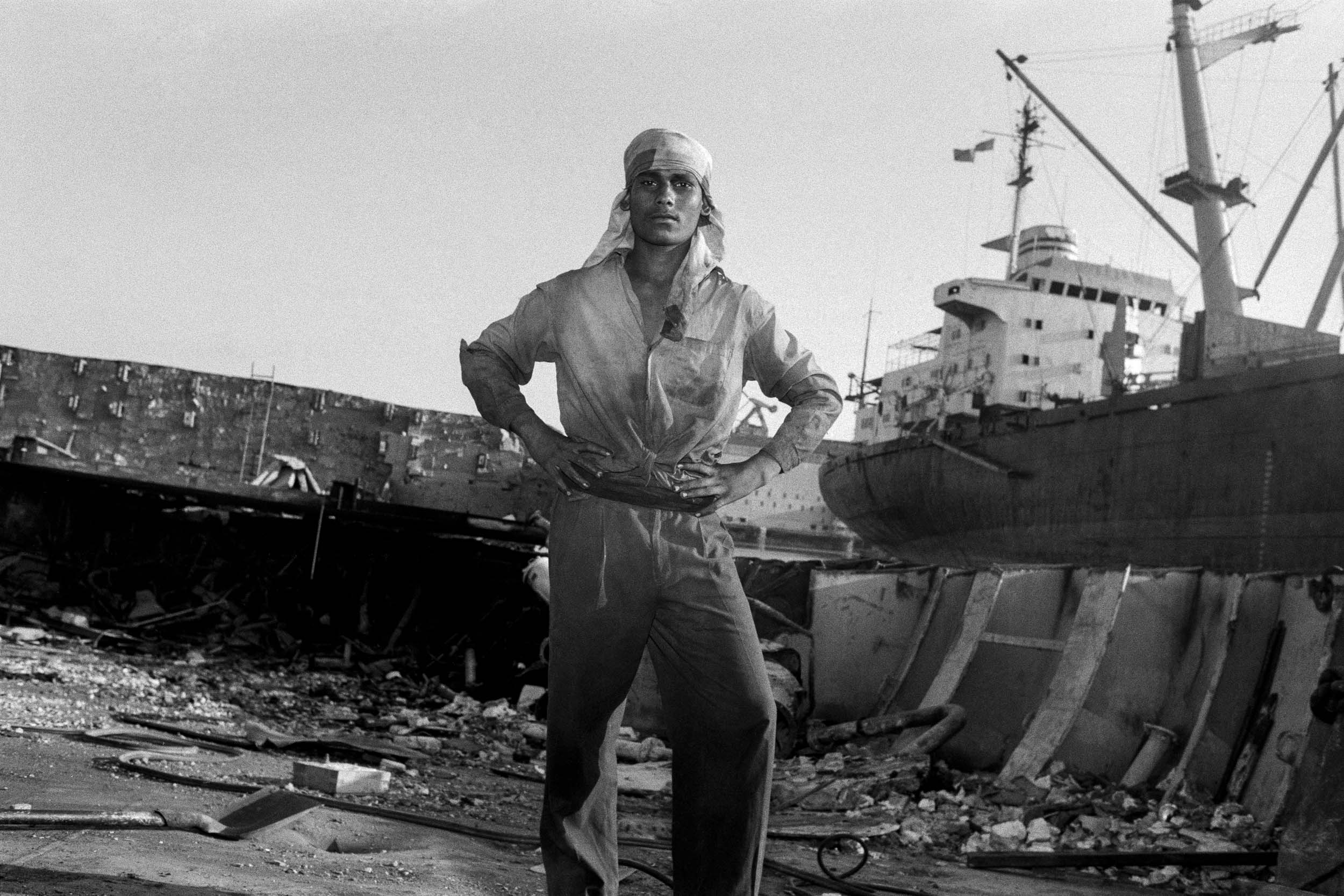

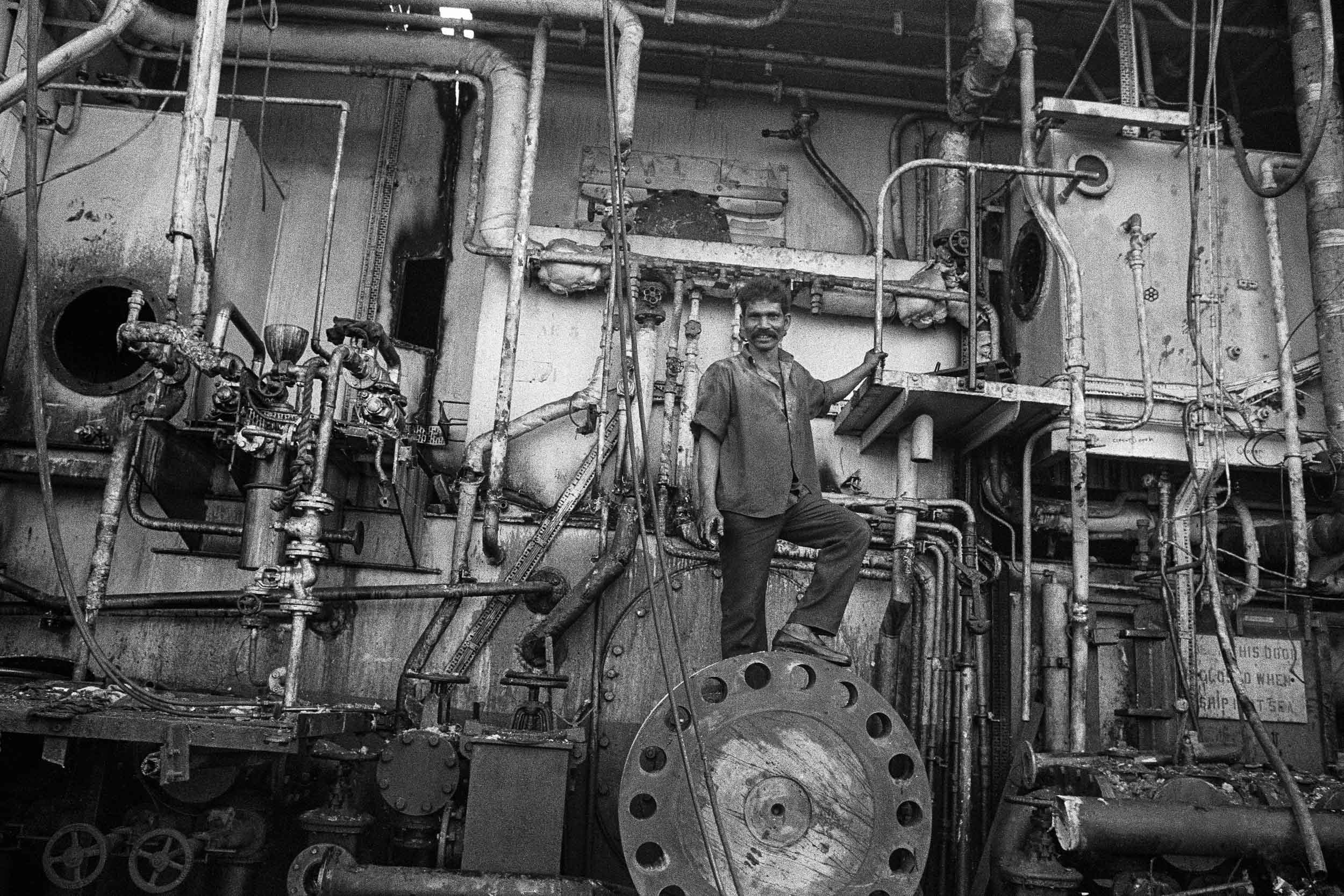

Men are crouched under massive structures of steel, using torches to cut pieces of metal that can be moved by two to a dozen men. They are on ships, cutting away at the bow and making their way slowly, over months, to the stern. Giant slabs of steel are lifted up by cranes and dropped to the ground where more workers cut the steel into smaller pieces to be sold to re-rolling mills. Some workers pry away the glass windows with a hammer and chisel. As the walls and floors are cut, what remains is only the frame.

In 2003, I visited the ship-breaking yards in Darukhana, Bombay, near Reay Road station. I was overwhelmed by the heat, the smoke from the gas-cutting torches, the bloodlike smell of iron and rust, the scale of the ships and the number of manual labourers required to dismantle them.

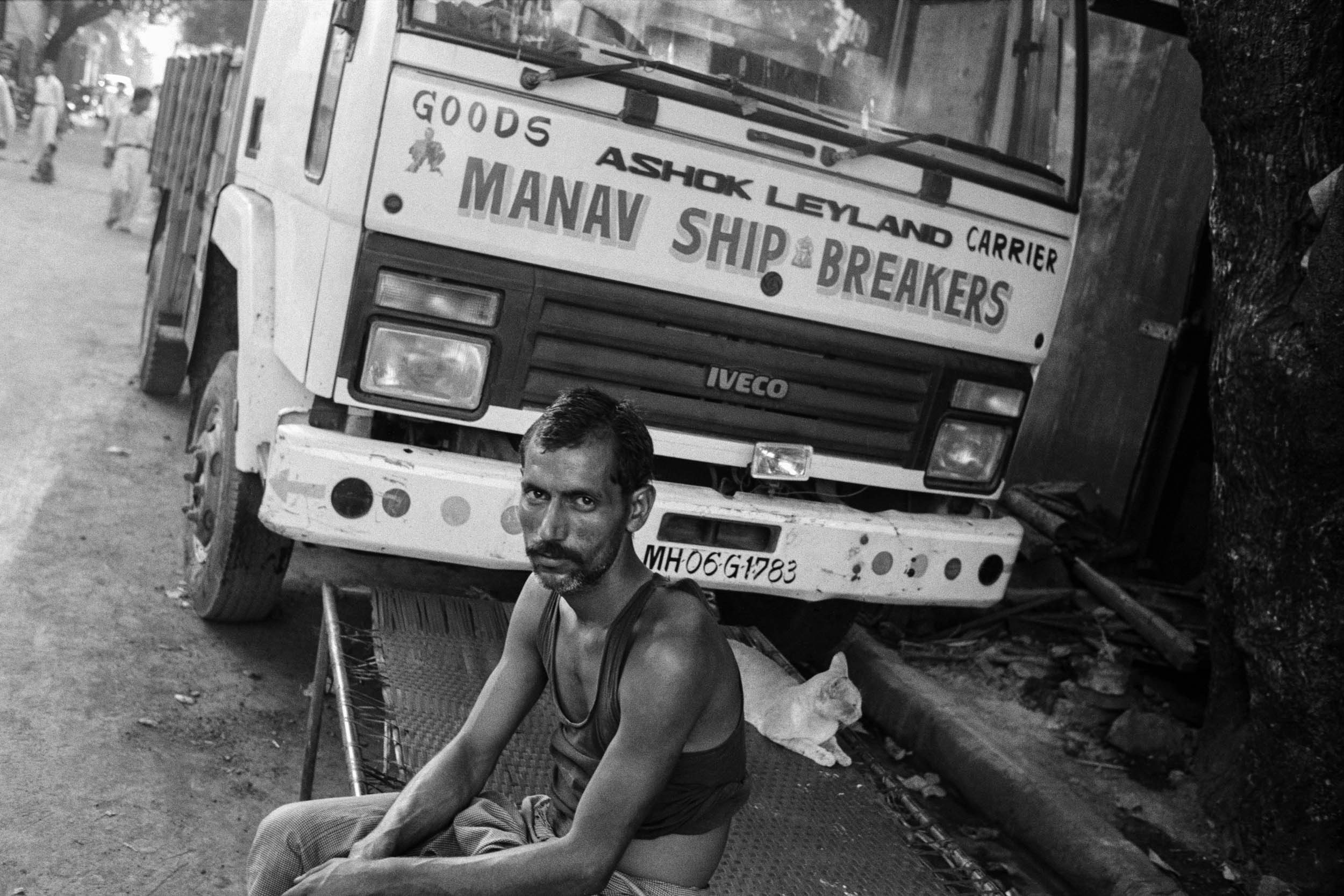

Each yard is surrounded by high corrugated-steel sheets, making it difficult to see anything through the door. Everything is loud: the trucks coming in and out, stacked high with sheets of steel and metal pipes; torches cutting the steel; chunks of steel falling from the ships and cranes prying the slabs. Accessing the yards is challenging: I managed to get into a few and spend as much time there as possible before the owners kicked me out. This would repeat itself over my two, week-long visits to the shipyard.

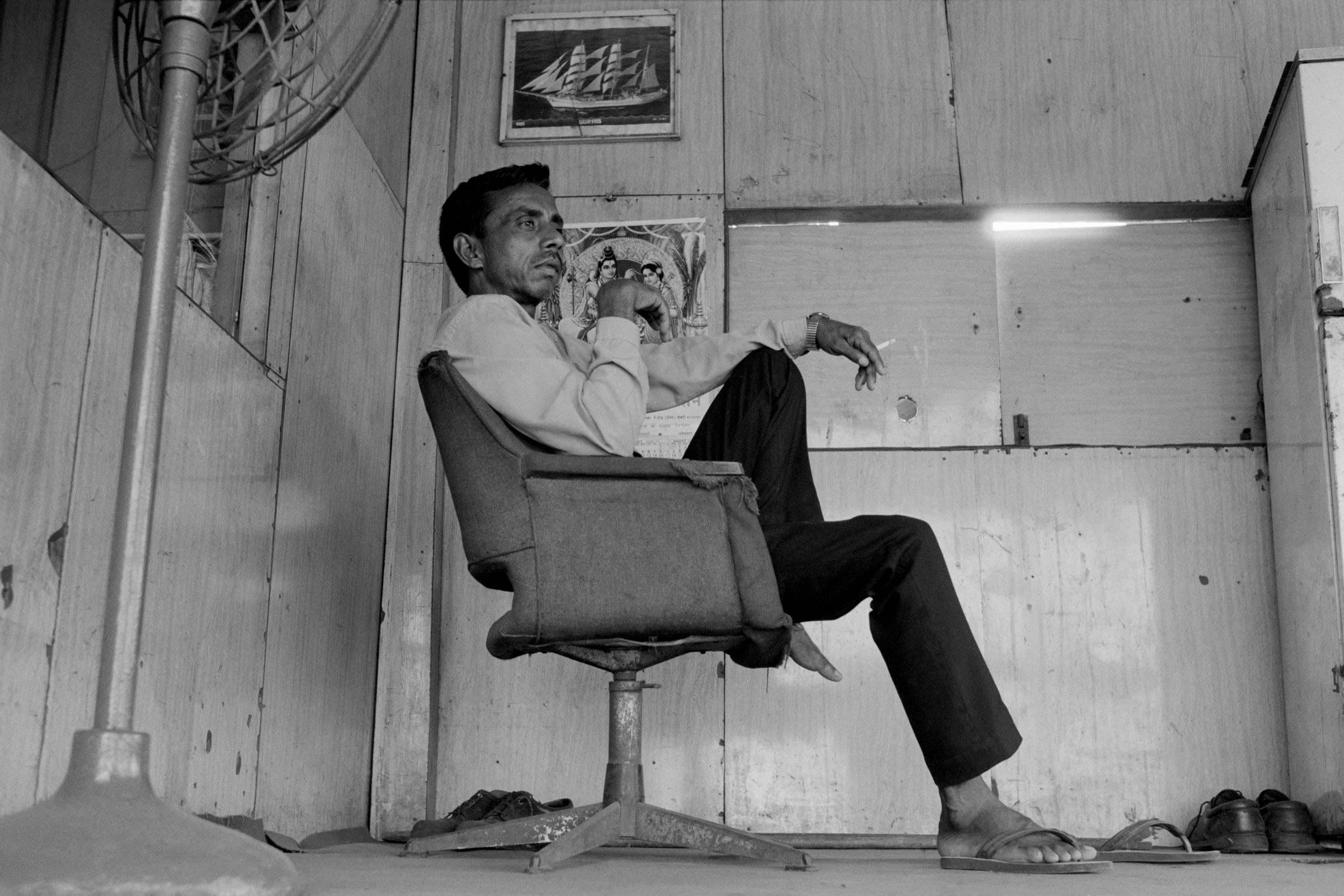

Workers live in makeshift houses near the shipyards and do not have much protective gear besides gloves and welding glasses. Some wear rubber boots, others only sandals. They strip bare the ships to recycle material, using only their hands and torches, in the process inhaling large amounts of dust. This work exacts an unthinkable and visceral toll on their bodies. The workers were suspicious about my presence. I learnt that many have died, either by falling off the ships or being crushed by large sheets of metal. There was a genuine fear that they would lose their jobs if the unsafe conditions at the yards became public.

India, Pakistan and Bangladesh are the three main destinations for decommissioned ships. The lifespan of a ship before corrosion varies from 25 to 30 years, after which the breakdown of metal renders it unsafe to operate. These three countries account for almost 67 percent of the ship-recycling market. The government of India recognised ship-breaking as a manufacturing industry in 1979. This industry hit its peak between 1994 and 2004 during liberalisation, when there were fewer restrictions on imports. At its peak, Alang, Gujarat, the largest ship-breaking site in India, employed approximately 40,000 people who broke down 350 ships every year. Optimal tidal conditions make these countries the preferred destinations to send decommissioned ships as they can be beached, saving a considerable amount of money for the seller and the buyer.

As a ship arrives at the port to be dismantled, the Customs Department surveys it for any banned substances. The Pollution Board inspects it next, to assess the toxic materials on the ship such as asbestos, tin and lead. Most ships built before the 1980s have been constructed with materials that release dangerous pollutants when broken down.

There is rarely a procedure to dispose of asbestos, resulting in workers having to break it down manually. In studies across countries where ship-breaking is practised, there have been increased reports of asbestosis which in turn may lead to mesothelioma, a form of cancer.

When the ships are beached, holes are drilled in the hull to drain the oil: this tends to seep into the ground and slowly makes its way into the ocean. Labour costs are low and environmental regulations are often not adhered to. The exploitation of migrant workers is rife at the shipyards: workers may owe a debt to the employer, and in the event of injuries or death, there is very little accountability.

Ships destined for breaking are “waste”, as defined by the Basel Convention, and in most cases are likely to contain hazardous substances. Following Basel, the European Union has recognised ships for dismantling as “hazardous waste”, as has the judiciary in India and Bangladesh. A Supreme Court of India ruling in 2012 declared a ban on the import of hazardous toxic waste and ordered the implementation of the Basel Convention, which imposed regulations for end-of-life vessels to minimise the health hazards and environmental risks of ship-breaking. This has led to a more ships being sent to Bangladesh and China, where there is now a large ship-breaking industry and where labour rights and health standards are often not enforced.

On my last visit a few months back, I found the yards empty and desolate. At one time there were close to 6,000 workers there, working day and night, but now the area resembles a ghost town. The wooden panels on one ship were still intact, the bed-frames had not been stripped yet and some of the fixtures had not been removed. As I entered a ship, I saw nude posters of women on the walls, a beautiful octagonal chess table, old tins of food and cutlery: the remains of a life lived on the sea.